2025, *** ON NOW *** Why am I me? *** Simian ***

Simian 🙂 up until 12.04.2026

Why am I me? is Laura Langer’s first solo exhibition in Denmark. For the show, the artist transforms Simian’s main exhibition space by means of an architectural intervention: a corridor-shaped sequence leads the visitors in a winding movement through a dense display of her work, making use of the venue’s scale to gather and rearrange in one single space a large number of paintings in a non-chronological order. Many of the works have been taken out from storage for this occasion to be reactivated, addressing, among other things, questions around speed of production, circulation, personal motivation, and public evaluation. The setup forces new connections and dialogues between the works, highlighting the heterogeneity and diverse visual languages throughout Langer’s painterly practice. Retracing the artist’s development over the past decade, Why am I me? facilitates a reflection on the works’ internal logic and changing meanings, while also pointing beyond the present moment. More than simply displaying past works, the exhibition is an introspective gesture, an exercise in self-inquiry, and an attempt to understand and integrate the many threads of her evolving artistic identity.

The order of things

The body vaults forward and back, an unlikely inverted pendulum, requiring infinite adjustments, like holding two linked broomsticks balanced vertically on the tips of one’s fingers. And with this movement comes rhythm, intentional navigation, space as a function of time. It is by automatically performing this feat of ingenious physical engineering, almost alien to its form—by walking upright, eyes forward, taking many steps—that the visitor will encounter Laura Langer’s exhibition, Why am I me?

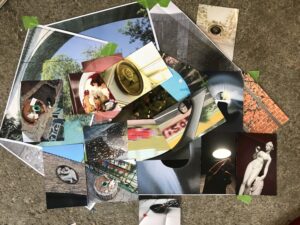

The following exhibition comprises a selection of paintings taken from the artist’s exhibitions thus far, along with unexhibited paintings from her studio storage. Since she works primarily site-specifically, there is an unlikeliness to Langer’s gesture: she is apparently disarming the works of their context and power, depriving them of the architectural homes that gave rise to their existence. Are the works rendered homesick—a theme that evidently preoccupies Langer, as two of her former exhibitions were thus titled—or are they merely away from home, for now? However alien, or alienated these paintings are, she has not deprived them of context, but has given them a new one, proof of their openness and adaptability.

Within the huge room of Simian, the artist has chosen to build successive corridors to act as the new architectural context for her works; on the surface, this is a plain, practical choice. The corridors, one after another, serve the purpose of creating as much white wall space as possible—the white wall being treated as the most neutral of all exhibition forms. Within the straightforwardness of this choice, however, lies a definitively assertive and dominating structure: the straight, and the forward: 1) a timeline, a compulsion to linear order; 2) an unknown number of corridors, the compulsion to be in the here and now, with what is in sight; and 3) a dead end, the compulsion to repeat. And within the visitor’s required revisiting of the timeline of paintings, in the same order but backwards, there is symmetry.

To produce this show, Langer has gone back over her oeuvre, and engaged in an editing process. The works are not shown chronologically nor in their original series. The hanging order is a product not of rules nor of a system, but of the artist’s own intuitive choices. There is no categorization, no hierarchy, except order. She is far from the end of her life as an artist, and yet she has taken this moment, almost arbitrarily, having reached a certain point of accumulation which produces both the desire and the ability to look back, revisit, and choose; and in this process to ask Why?, to assess, to reminisce.

I am interrupted now by the sound of gagging. I look down at the infant at my breast who is choking on a mouth too full with milk. This sight used to alarm me, and I would hold him upright, apologising and wiping his mouth. But I have since learned to let him be. I have learned to see this choking on liquid as a harmless part of his own learning, through which he will develop his gag reflex, in order to one day chew and swallow solids safely.

There is nothing arbitrary about Langer’s choice of installation architecture. It is an economical choice. During the planning of this show, she found herself at the junction of two problems: one of funding (no budget to produce new works) and one of storage (the threat of losing her existing storage, the question of where to put all the paintings already made). The resulting design is tightly packed like the small intestine, like the brain, where storage must be efficient, organized in folds, gyri, and plicae, permanent ridges that maintain a high surface area to be rendered visible, or permeable, or available for the transmission of signals.

It is not a coincidence that Langer’s first art education was in filmmaking. Her paintings, to me, have always been, if not about perspective and time, absolutely animated and given life by their implementation. The Wheel painting series (2025)—hung in a sequence, each painting rotated an unknown number of degrees from the last—appears to spin on the wall, their gold surfaces applied by hand in marker strokes that also seem to move as they catch the light. Homesick (2021), a series of paintings of the artist’s face as seen from below, as if she is lying in the grass; the series is a timeline, a storyboarded dreamscape. Point of view again, the Never Titled (2020) series that asks “Und Ihr?”, points at the visitor, and accuses him. The rooster (2023) confronts too, and so does the trumpet (2019, 2020), both looking at the visitor straight on, point blank.

Editing, in film, may be thought of as the control of cycles of tension and release1. That is how I understand the choices made in Langer’s sequencing of her paintings through the corridors. That which is hung straight on at the end of the corridor, which the visitor approaches for the corridor’s entire length is not of the same temporal experience as that which is hung to the visitor’s left or right, requiring the visitor to turn towards it. And it must be noted that in the intestines, the coiled passageways cause chyme to spiral, which slows its movement for better absorption. The turns in the corridors must do something too; they must slow movement, induce pause.

Langer’s choice not to produce new paintings was an intentional challenge to the demand of the new. And yet it was nonetheless creative. What is creative is the act of editing. Cutting into an existing body to give it a new form. She did this once before too, on a different level, with the painting series Execution (2023): she cut up a previously exhibited painting of a disassembled skeleton (2021) and put it (the painting) together again, in a new order, across three separate canvases. Editing is a return to something made before, a displacement of perspective; and in it there is always judgment, pleasure, the worry “is that all there is?”, as well as dissociation, the sitting beside oneself of “who was I then, that I did that? That I was able to do that?”

Walking is a highly complex manoeuvre. Reflexes must be broken down, integrated, lost in order for intentional movement to take its place. There is an order to things. One step in a child’s development is the Raking Grasp, they use the whole hand, pulling the fingers along a surface toward them in order to pick up something small, like raking leaves. This is the rougher approach, less refined than the Pincer Grasp, two fingers that aim specifically at the object that wants to be held. Is it evasive not to be comprehensive, but instead to make a careful selection, and to hide the next work behind walls, corners? Why not put all the works in one big room to see them all at once, the lot of them, once and for all? But the Raking Grasp not only collects objects, it is a sensual exploration. The baby’s hand swipes across my mounds of skin as he drinks. He makes windmill formations, burying his hand over and over into the folds of my soft sweater, and looking me straight in the eyes. There is nothing arbitrary or neutral in Langer’s choices: in order to be with a developing thing, a thing developing so quickly, a great intimacy is required.

The baby is crying in a room—dark but for a big black lamp, which faces into the room. I pick him up in a swaying motion and continue to bounce and sway. He turns his head and sees his shadow and mine together, a large black shape on the wall. As we move, the shape moves. He stops crying. He is in this moment discovering, and is comforted by his discovery of a correlation, indeed a causation, between what is felt in the body here and what is seen with the eyes, at a distance, there. As one walks through the exhibition, the paintings come into and out of view, the movement of the body causes a concurrent movement of the sequence of paintings, creating a timeline, the speed of which the visitor controls through locomotion. In fact, the rocking and swaying that lulls the baby is a simulation of what the baby felt in the womb (as I am writing this, I first write room, then whom) while the mother is walking. And so his learning to walk will be a learning to walk again, or learning again to be walking, now performing with his own body the many nervous, vestibular, and muscular functions that walking requires, and enduring the many effects of perception and cognition that that produces, in addition to locomotion.

There is an estrangement when looking at a baby. Babies are in a constant state of acquiring the fundamental movements and awarenesses of the human condition, which so quickly become automatic. The changes occur extremely gradually, day after day— first touching knees, later toes—and then in leaps—all at once a switch flips, and there is awareness. In this clear-eyed estrangement that watching babies brings, there is a sense of seeing everything, and of a return to one’s own forgotten past—and I find there is no such thing as universality, instead, at every stage of development and ability, there is a kind of totality, a collection of the whole mess of humanness into one tiny being. This makes me think about how Langer described herself making this exhibition. It was as if she had had all these experiences of making her paintings once before, then had to inhabit an event of spontaneous and total forgetting, becoming estranged from herself, to now look at the works again, to learn what they are a second time.

Liberty, mothers, execution, accusation, headlines, homesick: Laura’s is my favourite kind of art, the kind that is fundamental. Fundamental, in that it is open. It concerns everything and everyone can find themselves in it. An alien could come to Earth and connect with it. Fundamental, in that it contains chaos. Not that her works are chaotic, but that chaos can exist within them. They are the bedroom for the mess, the unconscious that structures the mind, the corridors that store the life’s work, the myth that holds the truth. And to take the messy room as the most concrete of these examples, this chaos is not at all disorder but layers of evidence, tracks laid down by the habits of days.

Rosa Aiello